A Two-Axis Approach to Villains

Designing the right antagonist for your game

Different games need different enemies, but if you are going to put a BBEG (Big Bad Evil Guy/Gal) into your TTRPG, I’ve distilled out a few salient points from The Science of Storytelling to help you craft this character.

Inside

Two-Axis Villain-Hero Spectrum

Foul update

Two-Axis Villain-Hero Spectrum

How do we write villains for our TTRPGs? Well, as is so frustratingly often the case, the answer is surely, “It depends.” It depends on what kind of game we are creating. It depends on how we want the players to interact with the villain. It depends on what kind of fun we want to set up for the players. Creating frameworks for every possible villain is impossible—or, at the very least, outside the scope of this post. What I can do is present a framework that you can use to help you think about designing the perfect villain for your game.

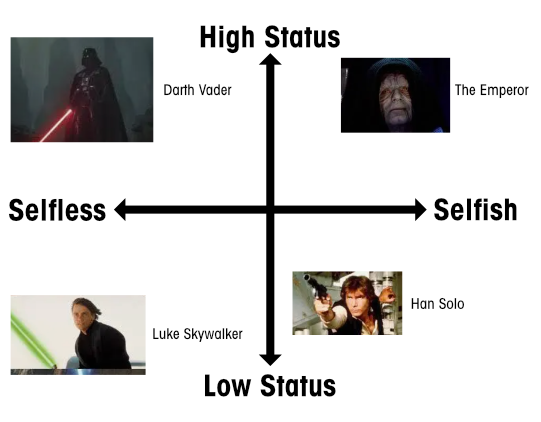

Allow me to present to you…the Two-Axis Villain-Hero Spectrum (cue the flashing APPLAUSE sign):

Just look at it. It’s…a little empty. We’ll work on that in a bit. For a quick reference, to save some word count, I occasionally refer to the quadrants with the numbering system I learned in math class:

Quadrant 1 = High Status, Selfish

Quadrant 2 = High Status, Selfless

Quadrant 3 = Low Status, Selfless

Quadrant 4 = Low Status, Selfish

Okay, let’s start with these two axes. First, and most important to our villain-making, is the Selfless-Selfish axis.

Selfless-Selfish

As detailed in The Science of Storytelling, there exists a reasonable line of argument that says the use of storytelling in the form of gossip was one of the primary ways that ancient humans were able to form and maintain cooperative groups. If someone was acting only in their own self-interest, the stories told about them would cast them as the villain of the group; if someone was acting selflessly, putting the needs of the group before their own, the stories told about them would cast them as the hero. This kept selfish behavior in check, allowing early groups of humans to grow and flourish.

This selfless-selfish distinction is possibly the easiest tool that a writer has to signal to a reader (or player) that a character is a villain. Even committing crimes or acts of violence does not trigger the villain classification as strongly.

An example. Let us take a quest that might be given to a party of adventurers:

A group of thieves has been preying on travelers in the area. You have been asked to go into the forest next to the village and capture the leader of the gang of criminals that hides there.

Sounds like a standard D&D mission right? We know who the villain is: the one that’s selfishly stealing from travelers.

One thing that was left out though:

The leader of the gang of criminals is known as “Robin Hood.”

Well, well, well, how the turntables. When the players learn that this criminal mastermind has been “stealing from the rich to give to the poor,” what will they do? This character just flipped to the other end of the Selfless-Selfish axis, making it very difficult for the players to consider him a villain. Will they still carry out their mission?

If the game designer/GM wants to drop the players/characters into this sort of dilemma, then the second piece of information (the “he’s actually not selfish” part) could be withheld for a period of time. Allow the players to prepare for their mission. Maybe even start the mission. Then, when they are fully committed to the mission, they get a hint that maybe not everything is as they were told. Maybe there are children in the gang’s hideout. Or maybe they see known, friendly NPCs from the village in the woods helping the gang or receiving gifts of stolen goods from the gang. Maybe the players have already captured Robin Hood when they get this information. What will they do now?

Status

The story of Robin Hood also plays into the second axis of our chart: Status. Humans are wired to root for the underdog. We want Jamal (Slumdog Millionaire) to win the grand prize. We want Rudy (Rudy) to get his shot on the field. We want Aladdin (Aladdin) to defeat Jafar. And we want Robin Hood to best the Sheriff of Nottingham.

Why do we root for the underdog?

Because we are the underdog. At least, in each person’s mind, they think that they are the underdog. Whether that might be objectively true or not is irrelevant. We want the underdog in a story to win (and attain the status of not being an underdog anymore) because it signals that one day we will be able to accomplish the same thing. Every person is the underdog of their own life story.

Back to villains. Let’s put some of the characters from Robin Hood on the Two-Axis Villain-Hero Spectrum:

We will ignore for the moment that in some versions of this story, Robin Hood is actually of noble birth and either forsakes his social status or has it taken from him. In most tellings of this tale, Robin’s status as an outcast and a criminal justify his placement in Quadrant 3 (the Hero Quadrant) on the villain-hero spectrum.

Let us take a moment to look at Quadrants 2 and 4. Friar Tuck has a bit of status as a member of the church, but he is absolutely selfless in his aid of Robin and the poor. Characters in this quadrant will often be “good guys” in a story, possibly patrons or abettors of the hero, emphasizing how the Selfless-Selfish axis is the dominant axis in this spectrum. In the opposite quadrant is Trigger, the assistant to the Sheriff. While he is selfish in how he helps the Sheriff oppress the protagonists of the story, and therefore a “bad guy,” the lack of status in this quadrant will mean these characters are often lackeys or henchmen serving the real villain.

This is all well and good, and you could take the spectrum as presented here and run with it. Villains are selfish and have status (whatever that means in your setting/story/game, often, but not necessarily, wealth or power). Easy. If you were writing an adventure meant to be run as a one-shot, that’s probably all you need. There isn’t enough time in that kind of a game for extensive character development.

But what if you had the time? What could you do with the Villain-Hero Spectrum?

Character Development

I talked about the importance of character change in a recent Ink & Dice post. I would be remiss to not talk about how we can combine that idea with this one. Let’s take a quick look at a few characters from the original Star Wars trilogy (spoilers, I guess):

Clearly, Luke is the hero and the Emperor is the villain. Han Solo must be a henchman of the Emperor and Darth Vader must be the patron that helps Luke along the way.

No? Did I get something wrong?

Well, for one thing, the characterizations that create the image above are not in sync relative to the story. When we first meet Han Solo, he certainly is a Quadrant 4 character, low status and selfish. However, when he comes to Luke’s rescue at the end of Episode 4, suddenly he switches into the Hero Quadrant as he selflessly jumps into the final battle of that movie. (He may bounce back and forth between these two over the course of the trilogy, but he spends more and more time in the Hero Quadrant as the plot progresses).

As for Darth Vader, he is a solid villain for 95+% of the trilogy. It is only at the end of the final battle of the series that Vader saves Luke’s life and throws the Emperor down that hole. As with Han Solo, Vader quickly switches from the right side of the spectrum to the left, and he truly is a high-status protector of the main hero of the story.

It is with these character changes that we get Drama™. If you are writing a longer adventure or a campaign, you may find that you want to create Drama™ for the characters/players to deal with. Here is one simple way to do it. Have a character start selfish and then become selfless. Now, the players need to decide how to deal with this character that they thought was a villain who turned out not to be.

The reverse works too. Have a high-status NPC begin by helping the low-status PCs, acting as a quest-giver or patron, but later on reveal that he is actually using them to further some selfish interest of his own. Again, the change in the character is where the story gets told.

Quest Goals

This is getting a little long, so I’ll be quick about how characters might deal with villains. Sure, in lots of stories (and games), the goal is to kill the villain. That’s great and all but not terribly elegant.

As much as we love to root for the underdog, we also like to see the high status villain brought low. Schadenfreude is a powerful feeling. This is why the quest of embarrassing a villain works so well. Kill the enemy, and they die once. Remove their status, and they die a little every day.

The same goes for altering the Selfless-Selfish axis. This is where the Redemption Arc comes from, and a quest to force a Redemption Arc, while it might need a fair bit of setup, is possibly the most noble quest the characters can undertake. As difficult as removing a villain’s status might be, changing them from selfish to selfless will be even more difficult, but success will be even more satisfying.

Foul Update

I’ve received the proof copy of Foul, and I’m doing some final proofreading. The risograph prints have been picked up, and they are gorgeous — everything that I had hoped for. I should be placing the order for the interior pages within a week, so we are on schedule to start fulfillment sometime in July.

The BackerKit surveys were sent out last week. If you have already filled yours out, thank you! If for any reason you need the survey email resent, please reach out to me through Kickstarter.

Thank you!

That’s it for now. I’ve got plans for another solo play report soon, à la my exploration of The Graveyard of the Armored Hearts. I’ve also got a couple more books on the TBR pile that might lend some interesting ideas to TTRPG design. We’ll see. Thanks for reading!

—MAH