Recently, I’ve been thinking a lot about foldies (TTRPG products that fit on a single sheet of paper and are intended to be folded in one way or another, i.e. trifold pamphlets or 8-page pocketmod zines). I talked a little bit about this in my last post when I laid out about my upcoming Liminal Grimoire project. In this Ink & Dice, I will lay down a bit more of what I’ve been doing on this project, including a deeper dive into writing pamphlet adventures.

Inside

What does a TTRPG adventure need?

Formatting your trifold pamphlet

Liminal Grimoire preliminary info

What does a TTRPG adventure need?

Back in July, I talked a bit about writing solo adventures. In that post, I boiled down the essential pieces of a solo adventure to the following:

Adventure Hooks (specific to the solo character/player)

Solo-Friendly Maps (either spontaneously generated or populated during play)

NPCs (specifically elaborating on motivations/reactions to the solo character)

When writing an adventure that’s intended to be used by a GM, there is room for a few other pieces of information. Maps can be more prescriptive, hooks can be looser to fit into an ongoing game, and NPCs can be given more specific agendas that will be hidden from the players until revealed during play.

But how much does an adventure need? What are the minimum pieces required to present an adventure? Well, let’s start at the beginning.

Introduction/Set-Up/Hooks

Since we are writing this adventure to be used by a GM, we can unload a few of the details up front:

What is this adventure about?

What hooks might pull the PCs into this adventure?

What backstory does the GM need to know about?

This is where I usually spoil the central conflict/theme of the adventure. Adventures should be written so that a GM can run them. The GM should not need to figure out the answer to the mystery of the adventure. The GM should not be surprised by an NPC’s motivation at the end of an adventure. The GM needs that information up front so that as they read about the structure and locations of the adventure, they can be thinking about how they will reinforce that central conflict/theme along the way.

Adventures should be written so that a GM can run them.

Procedures

The next essential part of a written adventure is where the procedures for the adventure are laid out. Procedures include details for the following (when used):

Hex-/Point-/Dungeon-crawling mechanisms

How and when to insert random encounters

How to count down the clock of the adventure

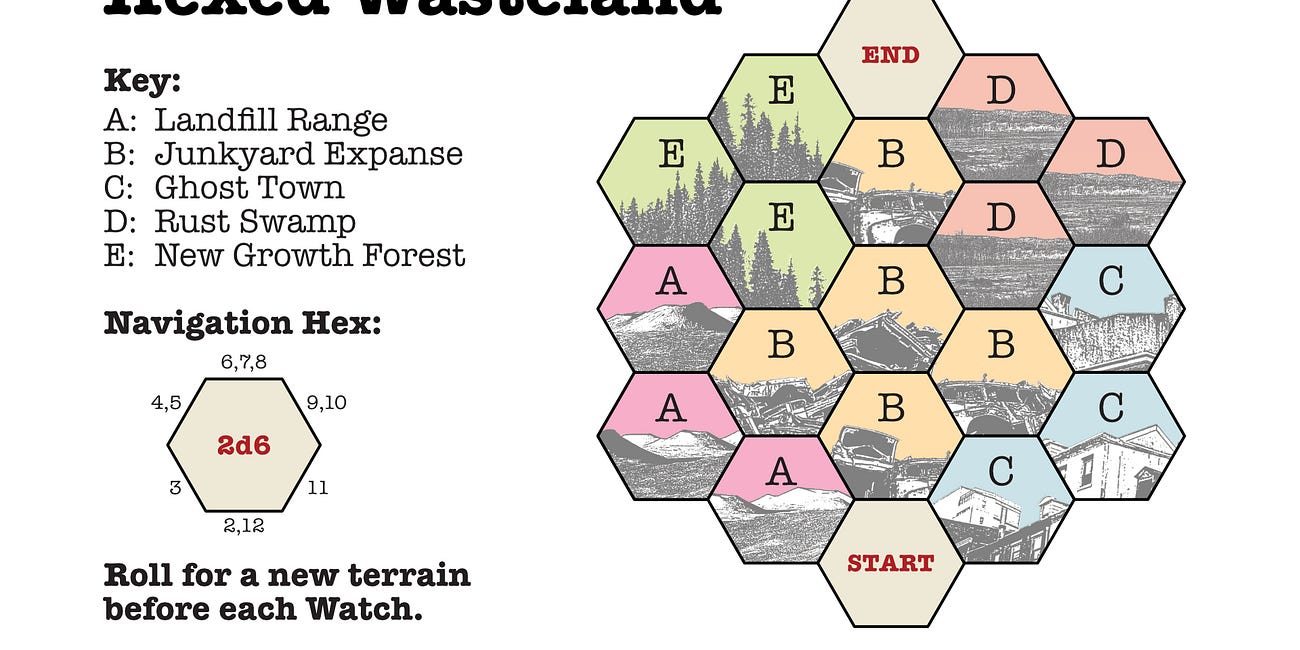

If your adventure is using a hexflower, this is where the adventure writer should explain the theory and practice of rolling and moving on the hexflower. I really like hexflowers, but their use assumes a high level of TTRPG mechanism knowledge from the reader. Explaining how to use one in an adventure requires a fair fraction of your word count. If you are curious about this particular procedure, I wrote about it recently here:

Hexed Wasteland

Exploration in TTRPGs can be defined as venturing into the Unknown so as to make it Known, progressing the story in the process.

Locations

Now we get into the nitty-gritty of our adventure: the locations. These might be:

Points on a point-crawl

Rooms in a dungeon

Locations on a hexmap

Hexes on a hexflower

Depending on your style and the context of your adventure, you might be writing a paragraph, a few bullet points, or just a few words for each location. There is wide variability, but I tend to include bits such as:

How does this place appear to the PCs (preferably by appealing to different senses, see Setting the Scene for more info)?

What/Who is here that the PCs might interact with?

Are there specific connections between this location and the general story arc of the adventure?

Action

This is a broad category, but it covers what happens with the PCs interact with the world of the adventure. It could include:

A sequence of events that might unfold if the PCs do not intervene.

Tables of random encounters.

Descriptions of non-random encounters (set pieces).

This is usually the hardest — but most important — part to write, as this is where the world is built and the fun of the adventure is created. Boring random encounters or uncompelling set pieces are a set up for an adventure that will never get to the table.

Appendices

Finally, the catch-all at the end. These will include various lists of relevant game-focused material, such as:

NPCs - Descriptions or stat blocks, along with motivations and connections, if applicable.

Factions - Descriptions and motivations of key factions, if applicable.

Bestiary - Stat blocks for creatures encountered during the adventure, if applicable.

Items - Stat blocks for items (magical or otherwise) found during the adventure, if applicable.

These are the sections that I start with when writing an adventure. Some get changed, some get cut, others get added, but I know that if I can fill out these headings, I have something playable — though that might not be adequate to say whether anyone will want to play it.

I use this structure so much that I have my own Scrivener template with these files. If you use Scrivener, you can download the template here:

Formatting your trifold pamphlet

Now that you’ve got your text written, if it’s in the neighborhood of 1000-1500 words, you are ready to make a trifold pamphlet adventure. If your text is much longer than this, your adventure is probably better suited for other printing formats (ranging from zine to hardback tome).

I go into this step with another template in mind. The trifold pamphlet has six panels:

The cover panel. This will be mostly cover art, and maybe some of your Introduction text.

The back panel. This is visible in the folded product, but requires flipping the unfolded product over to see. Here, I put my Set Up and Hooks — text that the GM will read but will not need frequent access to during play.

The outer folded panel. This panel is revealed when the cover is opened, but it is on the back of the product when it is fully unfolded and laid flat. I put information here that is not crucial to the story, but may be referred to by flipping the right panel closed during play. Most of the time my Procedures and some of my Appendices end up here.

The inner left panel. This is where the eye naturally begins reading once the pamphlet is fully opened. Here is where I usually start putting my Locations, which most of the time continue onto…

The inner center panel. Once I have gotten all of the Locations down, I move onto the Action information/tables. This will probably spill onto…

The inner right panel. The last of the panels to be read. Any additional Appendix information must fit after the Action info here.

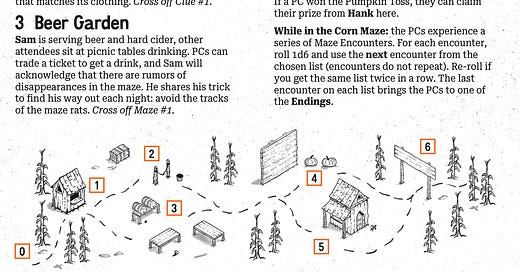

Once I have my text arranged across the panels, it is time to consider the map. Most adventures need some kind of map, but I won’t know what kind of space I can work with until the text is in place. For example, in one of my pamphlets for Liminal Grimoire, I put the location descriptions in, and then drew the map to fill the remaining space across the bottom of Panel 4 and Panel 5:

The same must be done for additional art. Spot art is not 100% necessary, since we have dedicated the entire cover to art, but pamphlets are not the place to play with whitespace — you can do that in your zines and books. If you’ve got a hole here, you might as well put something in it.

Liminal Grimoire preliminary info

All of these pamphlet thoughts have really helped me sort out my approach to the products that will be featured in Liminal Grimoire. Currently, the grimoire will be a custom-printed box including:

One Hour Photo (already available digitally)

Moe’s House of Meat (converted from The Lost Bay RPG to Liminal Horror)

Harvest Fest (see picture above)

Alone in the Dark 1 and 2 (solo tools for Liminal Horror)

The Hunger of Hours (The Backrooms meets The Langoliers)

Brine (probably featuring tentacles)

Witch’s Well (more info soon)

Liminal Horror Character Sheets

Liminal Horror Accomplice Sheets (for managing a party during solo play)

I am very excited about this project, and I hope to share the landing page link soon!

Thank you

That’s all I’ve got for this week. Hopefully you found this little outline helpful. Even if you aren’t publishing adventures, but instead writing them for use in your own games, I have found it useful to take a structured approach to adventure design. If you have your own tricks to getting started on writing adventures, I’d love to hear about them in the comments.

— MAH

It’s so interesting for me to hear about these processes and ideas. Great stuff!